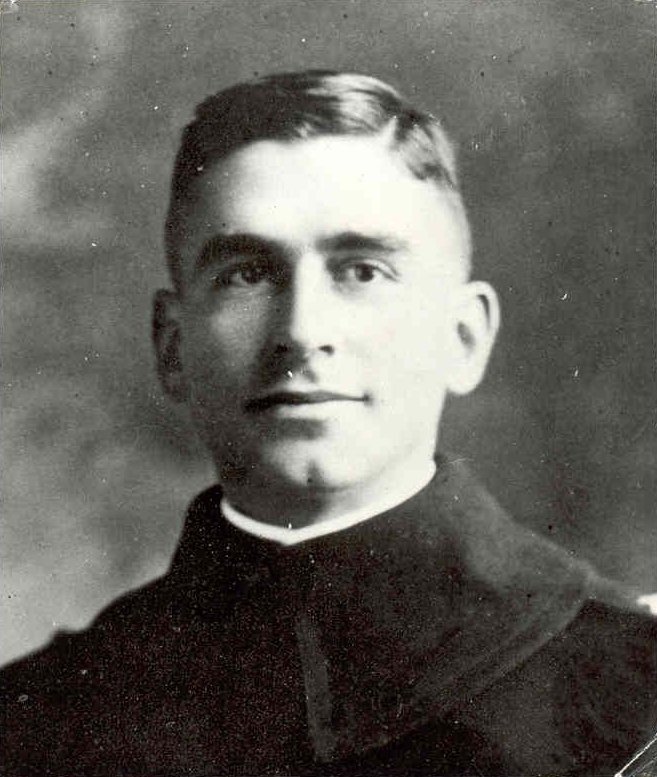

Edouard Victor Izac was born in Cresco, Iowa in 1891. His father was an immigrant from the Alsatian region of Germany, now France; his mother was daughter of immigrants of the Baden-Wurttemberg region of Germany. As a child, his dream was to attend the U.S. Naval Academy and serve as a Naval officer. His father, however, an outspoken Democrat, alienated the Republican Congressman who would appoint candidates to the Academy and thus put an end to this possibility. Young Edouard went to live with an older brother, in a different Congressional district, and obtained his nomination from the Democratic Congressman from that area. In 1915, at the age of 25, Izac graduated from the Naval Academy. The next day, he married Agnes Cabell, the daughter of Major General De Rossey Cabell, son of a Civil War Confederate officer.

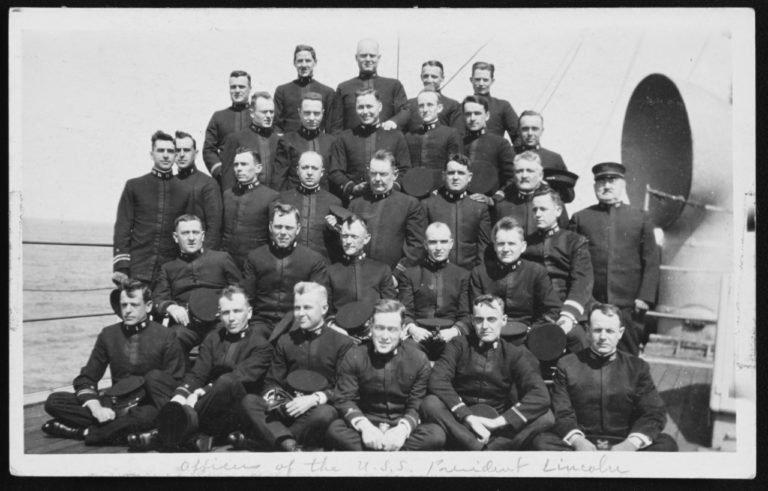

Izac’s first assignment was the battleship USS Florida (BB-30), but he was later reassigned to the Transport Service, ferrying U.S. military supplies and personnel to their destinations. Shortly after the United States entered World War I, he was assigned as the afterdeck gunnery officer on the troop transport USS President Lincoln. The President Lincoln completed five successful trans-Atlantic voyages, transporting 23,000 soldiers to France.

During the return voyage on May 31,1918, however, disaster struck. A German U-boat, U-90, fired three deadly torpedoes at the ship, sinking the President Lincoln in just under 30 minutes. While the majority of the those aboard were able to abandon ship before it sank, 26 officers and crew members perished. Lt Edouard Izac was taken as prisoner of war.

Another member of the President Lincoln’s crew, William Seach, himself already a Medal of Honor recipient for the China Relief Expedition in 1900, wrote about the incident in his unpublished journal. The Germans were searching for the captain of the President Lincoln or another senior officer among the survivors but were unable to locate either. In his journal, Seach wrote that in the process, he was being taken on board the U-boat when the Germans spotted Izac. They decided an officer of higher rank than Seach would make a better prisoner and tossed Seach into the water as they took Izac aboard. Across the open space between them, the men exchanged a glance; unspoken were the words “good luck.”

For the next five weeks onboard the U-90, Izac was allowed free range within the submarine and passed time playing cards with the crew. The captain and his officers spoke freely in front of him, assuming he did not understand them. However, Izac had grown up in a family that spoke German. While his level of fluency is not known, it is not unreasonable to assume that he had some command of the language. By carefully concealing this ability, Izac gathered valuable information on German submarines and their operation.

Through listening, observation, deductive reasoning, and a tremendous memory, Izac learned of the U-boat’s design, course and routines, its capabilities and movements, rendezvous points in the north Atlantic and other critical information. He was determined to escape and report his findings to the Chief of U.S. Naval Forces in Europe, Admiral William Sims. He devised multiple escape plans, at one point jumping from the window of a moving train as he was being transferred to a land-based prisoner camp. In that attempt, he was severely injured in the jump and brutally beaten upon his re-capture. Once in the POW camp, conditions were abhorrent and treatment of the prisoners was inhumane. When not in solitary confinement or in hospital recovering from harsh treatment, Izac was housed with prisoners from other allied nations and was able to verify much of the intelligence he had gained.

In early October a new opportunity to escape was presented when the Germans decided to remove all but the Americans from this particular camp. The plan was complicated: Izac led a small team to create a diversion which allowed the main group to escape through the front gate. In teams of two, the men set off for Switzerland. Of the 70 that escaped that night, only three made it to safety.

In the next seven days, Izac and his partner, Harold Willis, a member of the Layfette Escadrille, traveled over 120 miles, living off raw vegetables and whatever else they could forage. On the seventh night, they arrived at the banks of a creek that led to the Rhine River. The two men crawled on hands and knees down a rocky slope and past German sentries before entering the frigid water that carried them to Switzerland. The Swiss who found and sheltered them took them to the American Legation in Berne, where they arrived on October 15, 1918. On October 23rd, Izac made his report to Admiral Sims in London.

In later years, Josephus Daniels, Secretary of the Navy (1913-1921), was recorded to have said of Edouard Izac, “Well, as you know, they only captured one of us [and] couldn’t keep him.” Edouard Izac was the only naval line officer to be captured during WWI. In 1920, he received the Medal of Honor for his efforts while a prisoner of war.

In 1921, Izac retired from the Navy as a Lieutenant Commander due to injuries incurred during his time as a prisoner of war. Originally, he settled his family in southern California and after the stock market crash of 1929, relocated, temporarily, to rural France. He returned to San Diego in 1931, became a freelance writer, advocating for war veterans, specifically disabled veterans, and often wrote on the subjects of history and English. In addition, he sold ads for the newspaper. He was a vocal advocate of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal policies and programs and entered politics. In 1934 he made an unsuccessful run for Congress on the Democratic ticket. Two years later, however, he ran again, this time using his military record and status as a Medal of Honor Recipient, and won the Congressional seat; he represented San Diego, California, in Congress for 10 years.

Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, Izac was not in favor of United States entry into WWII and, although not vocal about it, it appears he was also against the internment of Japanese-Americans. In 1945 he was asked by General Eisenhower to join the Congressional delegation to inspect the liberated concentration camps of Dachau, Buchenwald and Nordausen and co-authored, with Senator Alben Barkley (D-KY and future vice president of the United States), the report titled “Atrocities and Other Conditions in Concentration Camps in Germany.”

Edouard Izac was not re-elected to Congress in 1946 and, relocating to Virginia, pursued his interest in lumbering and raising cattle. He later retired to Maryland and spent the last two years of his life living with his daughter in Fairfax, Virginia. At the time of his death in 1990, Edouard Izac was 98 years old, the oldest living Medal of Honor recipient and the last surviving recipient from World War I.